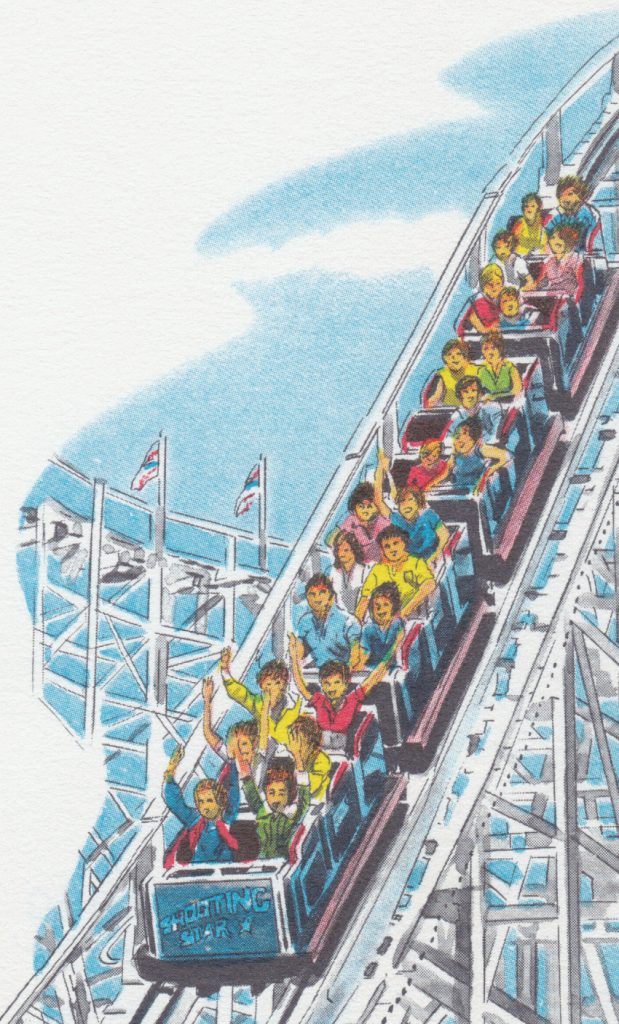

The Shooting Star didn’t arrive until May of 1968, about 48 years after Lakeside Amusement Park opened, but it quickly became the park’s iconic symbol until it closed on October 19, 1986.

The Shooting Star was designed by John C. Allen for the Philadelphia Toboggan Company. Allen once described building a coaster: “You don’t need a degree in engineering to design roller coasters, you need a degree in psychology.”

The Star cost $225,000 in 1968. Adjusted for inflation, that is about $1.94 MILLION in 2022.

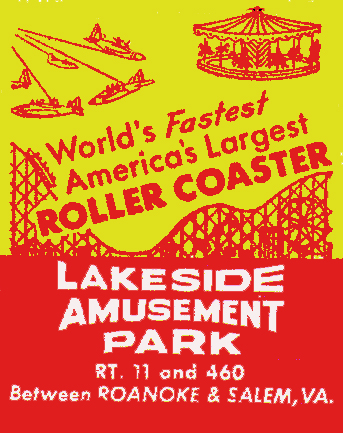

It was about 4100 feet long and close to 102 feet high. It billed itself as the World’s Fastest and America’s Largest Roller Coaster.

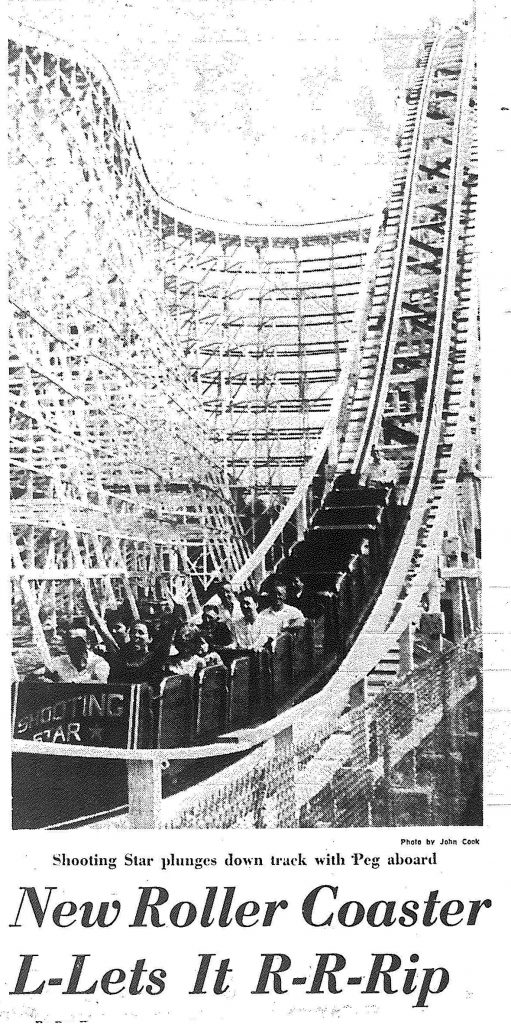

A Roanoke Times-World News reporter, Peg Foreman, was one of the first people to ride the Shooting Star. This story ran in the paper on May 3, 1968:

New Roller Coaster L-Lets It R-R-rip

by Peg Foreman

World-News Staff Writer

“You don’t have to go.” My editor said. “I’m not going to assign you to it, or anything… but that’s what made my perch atop the Shooting Star, 102 feet above the gravel at Lakeside Amusement Park, seem especially silly.

In the seat beside me was Sandy, my 10-year-old daughter.

I had picked her up at school so she would be able to tell the other children afterward that she was one of the first people ever to ride the longest and second-highest roller coaster in the world.

Besides, I needed help.

The ticket girl at the entrance stared at us and said. “I don’t think I’d want to be you.”

She handed us 2 little yellow slips of paper touting the new ride as the “most thrilling and fantastic roller coaster in the world today.”

It cost $250,000 to build, the paper said, and it is 4,120 feet long and 102 feet high

The little cars go 91 miles per hour at the maximum point . . .

That would be just around the curve, at my feet.

Beverly Roberts, the manager. said “hi.” when I

walked up to the Shooting Star’s ticket booth. Where he was adjusting the ticket machine.

“It doesn’t go that 135 yet,” he said. “It’ll probably take three weeks or so to reach maximum speed. To get the tracks smooth and the bearings well greased, you know. I figure it’s probably going about 70 now,”

That‘s comforting, I thought.

“It goes faster with more people in it,” he said.

Let there not be people, I prayed.

Two tanned teenage girls were standing by the cars, waiting for the bar to be raised.

“See those girls?“ Roberts said. “They skipped school to be the first ones on. They’ve been waiting there about 45 minutes.” A blond-haired man, who described himself as a roller coaster fan, said he’d been there for an hour. He travels from city to city apparently just to ride roller coasters.

“lt looks like a good one,” he said, squinting his eyes at it.

“We’ve still got a few more braces to put in,” Roberts said with a nonchalant air.

Something in the look I gave him must have given him a clue to what I was thinking, for he

added quickly. “nothing critical. If we don‘t put them in, the structure might start to bow in

about a year around ‘the curve there.”

It was 11 0‘clock, time to open the ride. I felt as I imagine what that fellow must have felt when the airplane door bIew open and the wind sucked him out …

Everyone got in line. The operator stationed himself beside the gate, his hand on the ‘big lever.‘

“Wait a minute,” somebody said.” Let’s send the cars

around empty, um, first.”

“Good idea,” I said, nodding my head vigorously.

Everybody got out.

The empty cars lurched forward and climbed slowly, slowly to the top of the first

curve. Then with a tremendous roar, they came hurtling down.

“It pauses up there at the top,” Roberts said. .

I nodded.

“Ow! It’s loud,” Sandy said.

It was the first word she had spoken after “goody.” She said that when I drove her away

from school.

The cars, seemingly none the worse for the trip, drifted slowly back to “go” and everybody got back in.

“Let ‘er rip.” Roberts said.

The man let ‘er rip.

“Nobody can fall out now can they, Mommy?” Sandy said.

One of the tanned girls threw both hands in the lair as we rounded the curve. The cars paused and swooped.

Scream, Ooh. Yelp. Grunt. Arrgh. My heart had taken a wild leap up and was obviously trying to claw its way out my ears.

The girl still had her hands in the air. Her brown hair was flying but the back of her head looked bored.

We were climbing again. Taking off for good, it looked like there was nothing ther-r-r-e . . . scream. Duh. Yelp. Grunt.

Arrgh.

“Mommy! Mommy! Mommy! It is jumping off the track!”’

And it slowed down. and Sandy said. “Hey, this is fun. How

many times do we get to go around?”

Everybody got out, except us.

I couldn’t.

“Can we go again, Mommy? Can We?”

“Yes.” l squeaked. There wasn’t much choice, really, was there since my fingers were glued to the bar.

The blond-haired man climbed out. “How was it?” I heard myself ask him, a reporter to the last.

“’Oh,” he said. “My palms got sweaty. Is that good enough?”

We started around again.

The tanned girl said, “it wasn’t much,” lowered her hands and with a twitch stalked away.

“Here we go. Here we go!“

Sandy yelled “I think twice will be enough for me, I think. I’m not sure, though.”

We went up, down, up, around, over, under, and back.

“Can we go again?” Sandy asked, hopefully.

“I can’t,” I replied. “I dropped my pencil. ’ ‘